|

|

|

Aranumono

Over the years, Aiko Miyawaki altered the appearance of her art by means of divers changes in both form and materials. Notwithstanding those apparent changes, Miyawaki has stated; “Unless you have an philosophy that you’re willing to carry through persistently, even obstinately, throughout your life, you can’t possibly call yourself an artist.” Her art has always revealed tension between transformations and a something that remains unchanging. Now her statement, quoted above, suggests that we consider the relationship between that tension and the philosophy that she is “willing to carry through persistently, even obstinately, throughout [her] life.”

What is the “something unchanging” in her art? Aranumono, “the invisible, or nonexistent,” Miyawaki once called it. Coming from a continuously productive artist, the expression, precisely because of its succinctness, is persuasive, even beautifully resonant. But what, in fact, does it mean? Unless we drag it into the mire of words, it will be consumed uncritically as a soothing myth.

Two problems hamper our attempt to get at the meaning of Miyawaki’s art. First, the starting point for determining the meaning of an artist’s work is usually to determine its context— the artist’s cultural sphere, aesthetic or political community, or, more loosely, community of interests. But Miyawaki’s career has made such an approach difficult, for even before beginning to work seriously at art she had spent some time abroad, and altough her first solo exhibition was in Tokyo, immediately thereafter she spent time working in Milan, Rome, Paris, New York, as well as Japan. We have no delimited geographical-social context to help us define her work. Nor is it definable as one pole of an antithesis between Japan and the West, or as an “ism” such as Minimalism or Conceptualism.

Notwithstanding, her work is not completely isolated; mutually influential and mutilayered relationships (however difficult to objectify), growing out of encounters and experiences whereever she has worked, have engendered definite points of contact with other contemporary art.

Lack of a clearly defined context begets another obstacle to, or a temptation to evade, understanding. In place of close analysis and careful explication of aranumono, more than a few scholars and critics substitute lyrical but superficial rhetoric. Instead of placing themselves close to the emergence of aranumono, and with words forging a path to that experience, they quickly cover it up with the conveniently poetic words.

These two difficulties are two sides of the same coin. Only by keeping closely to Miyawaki’s work—by observing them and engaging them in “conversation”—can I hope to weave my way between the two difficulties and to grasp some notion of the meaning she attached to aranumono, no matter how incomplete that may be. Below, I shall attampt briefly to do this, using several ideas as starting points. In the process, the interrelationships of Miyawaki’s art with variously intermingling historical, as well as philosophical, contexts may well begin to emerge from their present obscurity.

Light/ Traces

Let us begin with a simple observation.

When we look at Miyawaki’s works as a continuum, one aspect that remains consistent, even through various changes in appearance, is her concern with light. Consider, for example, her series of two-dimensional works, done around 1960, entitled WORK. For this series, Miyawaki used pigment mixed with powdered marble to create repetitive but differing bird-like patterns in subtle relief on a two-dimensional surface. It is said that when these works were to be exhibited, Katsuhiro Yamaguchi pointed out how their appearances changed under changing light and suggested illuminating them with a slowly moving light source.1) Although ultimately vetoed by the gallery, the idea was neither superficial nor adventitious. Moment-to-moment variations according the changes in illumination and in the viewer’s position are inherent in the works themselves, in the mixture of paint and stone (powder) and in the way it was applied.

Miyawaki’s profound interest in the effects of light on subtly undulant surfaces may remind us in some respects of the works of Agnes Martin and Robert Ryman, who also were producing monochrome paintings around 1960. But in contrast to the concern for brushwork (or pencilwork) so apparent in their work, Miyawaki’s art is characterized by the sculptural, plastic sensation she achieves by applying or stamping paint containing powdered stone on the picture surface. With Miyawaki’s method, the hard, material surface of the picture coexists with an indescribably soft vibration of light. Miyawaki’s subsequent works show her experimenting with variations on this combined effect.

In fact, her series of three-dimensional works using brass pipes, done from the mid to late 1960s, can be seen as a new development of the sculptural space already suggested in WORK, and her theme here too is the contrasting/ cumulative effect of the hard brass and the soft, vibrating light that envelops it. And marking the transition from the two-dimensional series of Work to the three-dimensional brass series is her 1964 piece Untitled; its square, centrally positioned mirror can be said to predict her three-dimensional brass works, whose surfaces are likewise mirror-like.

But although her works in brass are part of a continuum, they also show a degree of tension between the material and the effect of light that is not seen in WORK. This tension is owing in large part to the nature of brass, but it is also augmented by Miyawaki’s subtly staggered placement of the pipes. In other words, shifting light subverts the appearance of solidity even, at times, to the point of disintegration. The fact that the fundamental structure of the work is based on a multitude of orderly geometric shapes further emphasize the tension, to the point of disruption, between ideal shape and coexisting phenomenal light. This conflicting effects of substance, shape, and light, must have spurred Miyawaki to ceaseless experimentation, for it is my impression that this brass period produced works in the greatest number and the most various directions. The copiousness and diversity of their output, although not so successful in some cases, reveal the degree of Miyawaki’s fascination with light at this time.

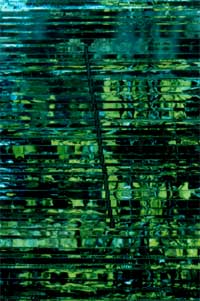

Unsurprisingly, Miyawaki’s preoccupation with light led her from brass to glass. Her series of works in glass, entitled MEGU, experiments even more radically with the opposition between light and the hardness inherent in glass. In these works too we see light subverting the solid regularity of the geometrically stacked glass plates, dissolving them and reducing them to illusions.

Significantly, the title MEGU means “to split” in the dialect of Okayama, according to Miyawaki, who has incorporated the act of splitting into the creative process. As the artist said, it takes a single forceful stroke (a split rather than repeated cuts) to create a transparent cross section in a glass plate. The act of splitting, however, introduces not one but several lines of force into her work: the force of the split not only cleaves the plate but creates subtle flickering traces on the surface of the cross sections. In several works of the MEGU series, we can also see holes pierced through the central area of glass plates. These traces, while floating within the transparent space of the stacked glasses, interact visually with the cross sectional edge.

The application of the paint in WORK and the positioning of the brass pipes likewise show us traces of the artist’s hand. In MEGU, however, the traces evoke the concentrated delicate violence of a single moment. We look at the cross sectional edges of the split plates and hear the sharp sound of glass breaking. Out of the work’s present facade of silence and immobility, the severed edges “speak” to us of a past moment of forcible action.

Voids

Miyawaki’s other works of the same period likewise embody the idea of action or “event.” For example, in 1977 Miyawaki split a beautiful triangular pillar of black granite into three. This work too is entitled MEGU. It is paradxical, in that the spaces created by the split are not material part of the work, though within its boundaries. Miyawaki’s interest in voids —vividly apparent in this work— is actualy as consistent as her interest in light; it is apparent in the valleys of paint in WORK, the holes of the brass pipes, and the transparent empty space of glass.

A series of about the same time, called STUDY OF HOMOLOGY, manifests the same fascination with voids. The works can be interpreted, with equal plausibility, as incisions in brass or as brass intrusions into the voids. These pieces have the air of a more methodical reconsideration of the nature of “splitting” and “void.” By incision, a cube becomes two quite different shapes, which when placed together naturally recombine into a cube. What is important in this is the viewer’s sense of the process. We are being deliberately shown the process of substance being transformed to void and void being returned to substance. By thus incorporating the very mechanism of creating traces into a work, Miyawaki has introduced temporality into her art.

What, by the way, are “traces”? Above, I have used the word in a material sense, to refer to the signs of physical action on a substance. But “traces” can equally well be used in a temporal sense, to refer to signs of the past existing in the present — the sense already implicit in the physical sense.

When the semiotician Charles Peirce classified signs into trichotomies, he categorized the traces left by physical contact or relationship between objects, such as footprints, as “indexes.” The essential quality of the index is its instantaneity or simultaneity.2) For example, a man cries out and points at a bird in flight. The relationship between finger and bird, which can exist only in that moment, is an index. Similarly, a footprint is an index, being a sign produced by an instant of contact between objects. Therefore, according to Peirce, an index is a sign characterized by simultaneity or physical contiguity. This, however, is to define the sign only from the point of view of its production. From the point of view of one who interprets the sign, it is an introduction of the past into the present—a strange phenomenon indeed, when one contemplates it.

Photography

As I noted above, the works called MEGU present a past action arising within a present stillness. But the medium that best typifies the strange, evocative power of the index is photography. Such writers as Rosalind Krauss, whose analyses of photography are inspired by Peirce’s notion of index, and Roland Barthes, who pondered the intense evocative powers of photographs from a different viewpoint, have as their common starting point the vivid experience of past as present when looking at a photograph.3) The concept of “index,” indeed, creates a bridge between traces and photographs that may help to interpret the works of Miyawaki. Miyawai’s habit of leaving detailed photographic evidence of her activities, including everyday encounters, seems to me unquestionably relevant to her art and illuminating to our interpretation of it.

Both the works she has created and the photographs of her seem to be informed by the desire to make an imprint of life as an unceasing present. The action that created the imprint itself ocurred in a present that is now past (dead), but the imprint itself imports that past action into the present, into the moment in which it is perceived. The index as the site of that transaction is the hinge that links Miyawaki’s works and photographs. Another of Miyawaki’s projects, carried on in parallel with her MEGU series, is suggestive of the same transaction: it is a mesh pattern, continually added to, drawn on a long paper scroll. Each unit of the mesh, seen individually, is mere present, without past or future. As part of the continuum, however, each existing (dead) unit participates in all the others, including the one in the act of being drawn, i.e., the present. The same fundamental idea—that separates units take on additional, transcendent meaning as parts of a continuum—is found in MEGU, in WORK, and in the pipe works, and also informs the artist’s daily repetition of photographing and being photographed.

More than any other, the medium that makes possible both the traces and the photographs is light. It is the light playing on Miyawaki’s works that evokes their ever-changing present for the viewer. That same light is also the physical medium by which the photograph, being an imprint of the world made by light upon photo-sensitive paper, imports a sign of the past into the present. Correspondingly, Miyawaki’s works, enveloped in and emanating light, undergo moment-by-moment transformations and exist always as a reflection of the here and now.

Sound/ Vibration

Miyawaki’s works introduce yet another layer to the experience of the present —its indexicality not necessarily, in this case, connected to the past. Like the play of light and the traces of force, the sound of the work gives an extra dimension to her art. Perhaps “sound” is better understood as “silent vibration,” emanating from the work and physically enveloping the viewer. Probably the morphological similarity of brass pipes to musical instruments is what first suggested to the artist herself that sound was an element of her work. In MEGU, sound is even more vividly present as an attribute not of shape but of action —the act of splitting.

This sensation of a silent sound is profoundly and closely related to the experience of an artwork in the present. The viewer’s sensation of resonating with the work distinguishes Miyawaki’s work from Minimalist sculpture, which plays mostly on the sense of sight and touch. In 1968, Miyawaki in fact produced a work literally entitled Vibration which actually produced sound. This was no sudden deviation from type, but a work in which the undertone that had coursed through the depths of her art had “broken the surface.”

At this point in the discussion I am reminded of Miyawaki’s metal and stone works inscribed “LISTEN TO YOUR PORTRAIT,” which she produced several variations.4) As far as I know, these are her only works that include words or letters. But why “LISTEN” instead of “LOOK”? This catachresis, incised repeatedly on Miyawaki’s works, reflects her fundamental approach to the “portrait” — to the human being as subject.

For Miyawaki, indeed, a human portrait is something not to be looked at but listened to (or to be listened to in addition to being looked at), just as we perceive in MEGU the sound of splitting. In particular, Miyawaki’s LISTEN series seems to resonate with the ontological investigations of philosophers such as Heidegger, who often used aural as well as visual metaphors when discussing the meaning of Being.5) In this regard, I should like to touch briefly on two points.

Body/ Language

First, both Heidegger’s and Miyawaki’s works explore possibilities of transcending the traditional relationship between subject and object (face-to-face, with a distance in between) by evoking the sense of hearing. With Heidegger, however, as he belongs to the philosophical tradition of hermeneutics, “listening” is inseparably linked to the experience of the poetic language. So the physicality, or bodily dimension, of listening is left unaddressed.

Second, Miyawaki’s work may relate more closely to the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty, who integrated Heidegger’s philosophy into his ontology of the body and further developed it even to the concept of the “flesh” of Being (or the world). Ironically, however, because he placed the body at the center of his philosophy, Merleau-Ponty omitted from his expositions the aural metaphors that had occupied an important position in Heidegger’s theories. Instead, his philosophy focused on reciprocality and reversibility of the sensations of “to see — to be seen” and “to touch — to be touched.” (Many Minimalist sculptors have therefore been greatly influenced by Merleau-Ponty in this regard.)

Although Merleau-Ponty tried to transcend the long tradition of Western philosophy, he was thus still rooted in what is now often called the “ocularcentric” traditions. In contrast, the perception of Miyawaki’s works calls for infusing the sense of hearing into the senses of sight and touch, and thus seems to penetrate Merleau-Ponty’s theory of the body at an oblique angle and opens up the possible path to a slightly different destination. Could it not be that what lies at the intersection (or blind spot) between Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty is the space of “listening” where words and body crisscross each other? This dimension of “listening” which can be reduced neither to body (sound) nor words (meaning) is therefore an unclear flickering between the two that can never be objectified. Is it not possible, then, to describe Miyawaki’s UTSUROHI (a moment of movement) as a series of works emerging from this indiscernible flickering? In UTSUROHI’s flexible compositional system and the way in which they cut and tie the world, I perceive an abstract “grammar”; in its site-specific variations producing different tones and rhythms at each site, at the same time, I hear its “song.” 6)

Modernism/ Postmodernism

The interplay between hard material and insubstantial play of light links Miyawaki’s works of brass with UTSUROHI. That is to say, UTSUROHI also consists of light subverting the substantiality of material (chromed steel wire). But the lines of UTSUROHI, thin, bending, and vibrating, sometimes even become pure traces of light and shadow. At the same time, the voids became an integral part of the composition.

The history of twentieth-century sculpture is in one sense a history of challenges to the traditional concept of sculpture as an enclosed mass and volume separated from the surrounding space. Significant among these challenges was the incorporation of voids into the interiors of sculptures. Beginning with Picasso in his relief Guitar of 1913 and continued in Tatlin’s Corner Relief, the Russian Constructivists, Henry Moore, Anthony Caro after World War II, and many others incorporated voids as a compositional element in their works. While these various attempts provided a general historical pre-condition for Miyawaki’s incorporation of the void, they are not directly tied to UTSUROHI.

Rather than comparing Miyawaki’s art to those historical precedents in the use of the void in sculpture, it may be more fruitful to see how it relates to the work of artists, who, since the mid-sixties, have expanded their fields of expression to various forms of “non-sculpture.” In particular, how does Miyawaki’s art relate to the postmodernist trend in the category of (non-)sculpture which Rosalind Krauss pointed out in her treatise, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”? 7)

According to Krauss, sculpture reached a point of diffraction in the 1960s as a result of the exhaustion of the modernist pursuit of its autonomy (as an autonomous whole separated from any specific place or time). In other words, through the sculptural activity of the 1960s, the essence of sculpture, which until then was thought to be determined by an internal logic, became something that could only be defined through negative relationships to external entities —something that is not architecture and not landscape, for example. This development of sculpture into pure negativity, or difference, opened up other logical possibilities of its becoming, for example, both architecture and landscape.8) This expansion of the field of actual practice and logical possibility is what occurred throughout the 1960s, and the works of artists including Robert Smithson, Robert Morris, Michael Heizer, and Mary Miss were in fact experiments in that expansion. Their works attempted new relationships with their environment, to elude the traditional relationship with sculpture.

Krauss pointed out the “logical” aspect of this expansion and identified its transcendence of the “material-ism” of traditional sculpture as a mark of postmodernism. In other words, she asserted that the essence of sculpture no longer lay in the expressive powers inherent in a material but in sculpture’s external relationship with landscape and architecture. According to Krauss, the seeming arbitrariness of the materials used by postmodernist artists results from assigning priority to these external relationships, and the artistic activities that seem eclectic from the viewpoint of modernism are in fact logically consistent from the postmodernist standpoint.

Krauss’s analysis provided a new valuable epistemological filter in response to the emergence of postmodernism in “sculpture.” But her account of the progression from modernism to postmodernism as a rupture, a sudden jump from the material (or essentialistic) dimension to the dimension of structural logic, seems to me a little too clear-cut. Between modernism and postmodernism there lies (it seems to me) a “twist” that can be seen as either a continuum or a severance. Krauss’s theory has not dealt satisfactorily with this logic of the twist. And Miyawaki’s UTSUROHI is, I would argue, located precisely at the point of this twist. Let me explain.

First, UTSUROHI partakes of postmodernism by existing within landscape and/or architecture as an element that is neither one of these and yet impacts them both. At the same time, however, its structure derives from a profound insight into and observation of the properties of the medium. While subtly changing its appearance as well as its significance and effect according to location, it nevertheless does not lose its autonomy as a structure. In that sense, UTSUROHI is like a knot tying together modernism and postmodernism. In fact, if UTSUROHI emerged out of Miyawaki’s sustained dialogue with the material/medium since her works in brass and glass, we can even argue that her modernist reflection on the properties of the medium forged a path to postmodernism from within the work itself.

The self-reflective investigation that is crucial to the modernist conception of sculpture may stop at the discovery of its “essence,” but its also contains the inherent possibility of reflecting on that very essence and thereby going beyond it. The leap into the “logical” dimension proposed by Krauss may be thought of as such a movement carried to its ultimate conclusion. Thought of in this way, modernism and postmodernism remain connected beneath a superficial appearance of severance, and the development of Miyawaki’s UTSUROHI seems to illuminate the path of that connection.

It should be obvious to anyone who has experienced UTSUROHI that this work transcends works like MEGU in exploring even more profoundly the meaning of “body.” It is as if all its elements— light, vibration, void — have been determined within its relationship to our bodies, which it invites, rejects, penetrates, connects, binds, cuts, and envelops. The sparse structure of UTSUROHI and its flexibility and mobility, together with the aforementioned sensation of vibration, transcend the pattern of the dual subject-object relationship and cause to emerge a new body “field” that will necessarily differ among persons experiencing the work.

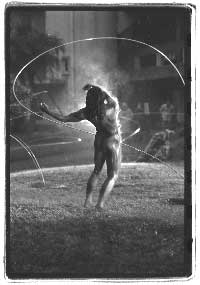

Once, the butoh dancer Min Tanaka gave a dance performance with UTSUROHI sharing the stage. I doubt there could ever be a more stimulating stage setting for a dancer. Nevertheless, UTSUROHI does not compel each one of us to dance. In fact, my own experience of the work is a humble one, which, figuratively speaking, lets me recapture anew such everyday experiences as walking or standing. UTSUROHI is a field that regenerates lost vibrations, or generates unseen vibratinos, in the various postures we humans experience in life, like dancing, walking, or standing. And within that experience, each one of us is challenged to “listen” to our portrait. Without doubt that aranumono (the invisible or nonexistent) is nothing other than your portrait, which you will hear if you listen.

(Translated by Yumiko Yamazaki, edited by Naomi Noble Richard)

This essay is reproduced from no beginning, no end Aiko Miyawaki 1958–1998 [published by the Museum of Modern Art Kamakura& Hayama, 1998]

Copyright (c): The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama

|

|